The Iconographic Tradition

Alan Ogden, Revelations of Byzantium, Appendix. April 2001.

ISBN 973-9432-32-8

Viewing Orthodox ecclesiastical art for the first time presents many people with a formidable challenge as to how to understand the nature and meaning of iconography. The following is a short guide, illustrated with the "writings" of Silvia Dimitrova, a contemporary icon artist from Pleven in Bulgaria. Her paintings represent the continuing tradition of early Christian art and it is apt that she is currently working on a commission for Wells Cathedral in England.

"The icon is a song of triumph, and a revelation, and an enduring monument to the victory of the saints and the disgrace of the demons." (John of Damascus, On Icons, pp. 676-749)

"The Tradition of the Church is expressed not only through words, not only through the actions and gestures used in worship, but also through art - through the line and colour of the Holy icon. An icon is not simply a religious picture designed to arouse appropriate emotions in the beholder; it is one of the ways whereby God is revealed to us. Through icons, the Orthodox Christian receives a vision of the spiritual world. Because the icon is a part of a Tradition, icon painters are not free to adapt or innovate as they please; for their work must reflect, not their own aesthetic sentiments, but the mind of the Church. Artistic inspiration is not excluded, but it is exercised within certain prescribed rules. It is important icon painters are good artists, but it is even more important that they should be sincere Christians, living within the spirit of the Tradition, preparing themselves for their work by means of Confession and Holy Communion."

To understand the interior paintings and external frescoes of the painted churches and the monasteries, it is necessary to return to the origins of Christian art, which is still to be found in the iconography of the Orthodox churches. Icons are Christian religious pictures, found mainly in Eastern and Southeastern Europe and Russia, and are usually portraits or scenes in the lives of Jesus, the Mother of God (the Virgin Mary), the Archangels - Gabriel, Michael, Raphael, and Uriel -, and the Prophets, Angels, and Saints, particularly St. George.

The artistic, stylistic, and spiritual origins of icons go back several centuries before the birth of Christ and continue until the beginning of the sixth century AD. Despite their initial antipathy to art in all forms, which was widely associated with paganism, and their preoccupation with the Second Coming of Christ, the early Christians lived at a time of serious social and economic breakdown when the old ideals of Roman republicanism were in rapid decline. Despairing at the injustice of a corrupt bureaucracy that presided over disorder and poverty, they soon compromised and accepted the concept of pictorial theology so the Church could reach the large numbers of people who could not read. The earliest art that is definitely Christian are the paintings in the baptistry at Doura-Europos in Mesopotamia. Only a handful of scenes remain: the Good Shepherd, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the Women of Samaria at the Well, the Three Martyrs at the Tomb, Christ Healing a Paralytic, and Christ and St. Peter Walking on the Water. These paintings were executed long before the introduction of Christian iconography, yet five hundred years later these scenes would occupy the least important places in the visual aspects of a church, if they were used at all. The Good Shepherd was dropped altogether.

In contrast to the historically recorded likenesses of St. Peter and St. Paul when they were in Rome, no actual image of Christ was passed down in the early Christian Church although there are two legends: in the Eastern Church, King Abgar's mandylion, a Greek word for hand towel which refers to the cloth containing the imprint of His face which Christ had sent to Abgar via Apostle Thomas and his friend, Thaddeus; and in the Western Church, the cloth of Veronica (vera icon - true image) used to wipe the sweat from Christ's face on the road to Golgotha. Neither story can be substantiated, yet both held the fascination of Christians for many centuries.

The earliest images of Christ's life were passed down orally, hence the strong relationship between hymns and chants and the compositions of icons, and textually through the gospels. This marked subordination to a text, the "literary imperative" characteristic of Byzantine religious art, accompanied by the shunning of individual creativity, led to the Painters' Manuals or Pattern Books of Mount Athos in 1468 and in Russia in 1552 (Stroganov). These were the rulebooks from which deviation was not permitted.

At one stage, the very existence of icons was challenged. In 725, the Byzantine Emperor Leo addressed the question: Is art the ally of religion or its most insidious enemy? Is the visual depiction of the godhead possible? And, if so, should it be permitted? Logically, he argued, if we accept the divine nature of Christ, we cannot then approve of a two- or three-dimensional portrayal of Him as a human being. At the time of Leo, icons were openly worshipped in their own right and occasionally even used as god-parents at baptisms. Leo's motives were almost certainly more political than philosophical and were an attempt to break the burgeoning power of the Church as well as to assuage the wishes of his Moslem army and allies.

After some debate, Leo ordered that all icons were to be destroyed and so both the beards of intractable monks and their great libraries were set on fire. During the iconoclasm a vast treasure of icons was destroyed or dispersed to caches in the far corners of the empire. It was sixty years before the conflict was resolved in favour of the iconodules and the art form reintroduced across the Orthodox Church. Under Theophilus, the debate flared up again and was finally resolved in 843 at the Council of Constantinople.

Typically, icons are painted (they are said to be "written" the way Scripture is) in tempera on wooden boards, sometimes with gold or silver covers to look like a book. This practice may have been introduced to protect the icon against the pious habit of kissing but it was also a way for rich benefactors to demonstrate their largesse to the monasteries. Unlike in much of Western art, there is no specific external source of light in an icon - the iconographer or artist starts with the darkest colours in each area and then adds the Light. Thus, for instance, the face of a saint, especially the eyes, becomes the focus. In their portraits of Christ, icon painters had the task of reproducing the ideal image - that is of combining the sublimity of His Divine Person with His true humanity. At the same time, the beauty of the humanity redeemed by Him was supposed to shine forward in the beauty of His image.

Although pictures in icons are images of human beings - icon actually means: "image as the likeness of a prototype or model" - the paintings have deep mysterious meanings. Richard Temple in his authoritative study of the interpretation of icons lists the following essential features that condition the inner meaning of icons:

The Idea of Self and Self-knowledge. There is nothing beyond or outside the self that cannot be known within. If I look at an icon of Christ (or an icon of a saint who by his saintliness has become Christ-like), it is Christ who looks at me. All esoteric teaching points to the fact that if I want to know God, I will do so by inwardly knowing myself.

The Divine Ray. The idea of higher and lower levels leads to the placing in the icon's composition of the various features and persons, according to the place in the cosmos to which they correspond. The "ladder ascending from Earth to Heaven" is as much within a man as outside him.

The Warrior. A "secret war" is fought within us between our spiritual development and the distractions of our senses and passions; our weapons are ceaseless prayer and self-mastery. Christ, the shepherd, guards the pastures of our heart and thoughts.

The Idea of "Inner and Outer" distinguishes the spiritual from the physical. The architecture that encloses space signifies withdrawal from the outer world and the awakening to the life within the inner chamber of prayer and active meditation.

Light. Physical light in dispelling physical darkness symbolizes spiritual light dispelling spiritual darkness. The illumination thereby transforms man's inner life.

Unity and Multiplicity. The disposition of the shapes, forms, rhythms, colours, and lines, together with the strong central axis and the balanced symmetry of the composition, have the effect of relating all these elements into a harmonious and single whole. Thus the icon is always complete and enclosed within itself.

Silence and Stillness. The precondition for understanding all of the above is silence and stillness.

Icons contain extensive symbolism, the idea of presenting abstract truths in an enigmatic way. For the peoples of the past, symbols were guiding lights in the shadowy puzzle of life, much of which was controlled and regulated by authoritarian social structures. For instance, since time immemorial, the sun has been revered as the divine symbol of energy, without whose rays, all life on earth - plants, animals, and mankind - would perish. Thus the halo behind the head of the human image represents the shape of the rising sun and the colour gold its light, a device used by the Egyptians and Persians long before Christianity.

Many of the symbols of the early Christian Church were as old as man himself. The mother and child theme can be traced back to Osiris and Horus from Egypt. The cave, a landscape feature which appears in many icons, was also the scene of the birth of Bhudda; Rhea's birth of Zeus in a cave in Crete; Venus's visit to Adonis in a cave; Mithras's birth in a mountain cave (indeed his followers worshipped him underground). Mithras was seen as sol invictus - the Invincible Sun; this title was then used by the Roman emperors on their death when they were taken by chariot to the sun and worshipped as the god of the sun. December 25th was the birthday of Mithras, natalis invicti solis.

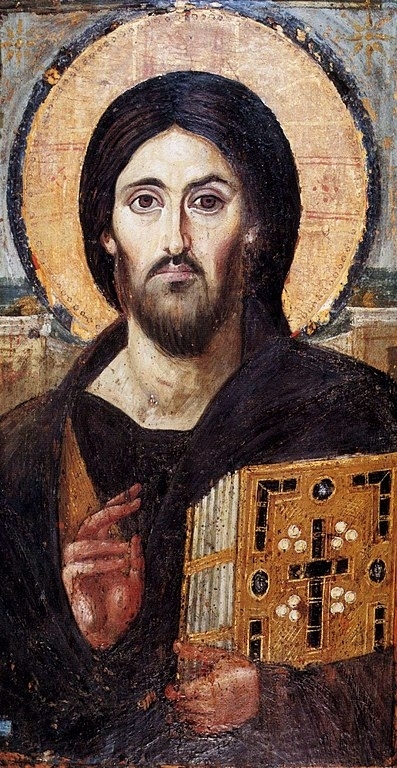

The first known icon is called the Sinai Christ, painted in the sixth century. This image of the Pantocratic Christ, the Ruler of All, survives today and is widely reproduced around the Orthodox world.

"Christ gazes on eternity while at the same time the onlooker feels that this gaze is directed intimately and personally on himself. Here the self is not the ego, the small self that belongs to the material world and to time, but the Self, the true I that came from, and will return to eternity. It is wisdom looking at itself; it is the self looking at itself. Thus we are brought to the threshold of the mystery of existence."

Looking closely at it, one can see a number of symbols:

the beard represents a teacher;

the book means knowledge and wisdom;

the cloak is the traditional garment of a wise man;

the halo - or solar disc - relates to the sun as the centre of our universe.

The symbolism of colours can also be seen in the purple cloak, purple being the colour of the elite as far back as early Peruvian and Mexican civilizations, indeed, together with blue, it was the colour of the Roman emperor himself (at Hagia Sophia, Christ wears a cloak of Lapis Lazuli). Green was used to represent earthly values and is the main background in landscapes. Yellow as the ancient calorific symbol of Jews and prostitutes is rarely used in icons.

The body language of icons - gestures, signs, physiognomy, and mimicry - can be seen in the gesture of holding the book of wisdom, the sign of the benediction with the right hand, the proportion of the head to the body (One unit of Nine) and the gentle scolding of the eyes. The gospels are usually opened at the verse:

"I am the light of the world" or "I am the door to the sheepfold." There are two main versions of the icon of the Mother of God: the Hodegetrian pose where Mary "indicates the way" as She points towards Her Son as the path of salvation and the Eleusa pose where She looks lovingly down on the infant Christ in Her arms, Her hands clutched around Him. In the latter, Her happiness is tinged with a sadness and foreboding as to the fate which Her child will suffer at the hands of man.

Icons are never seen as new in the sense of separate and recent. All icons of Archangel Michael for instance are seen as the same icon. They are all of the same reality, of the one icon. No icon is ever copyrighted - one may freely copy an icon since it is not an individual work but the one work. When an icon is finished, the writer of the icon may add to the back his or her name - "by the hand of" - but the image is never signed. No icon therefore belongs to the iconographer.

The symbolism of numbers in art stretches back to early civilizations in China, Babylon, and Egypt and has considerable relevance in the composition of Byzantine paintings and icons:

One: The Uncreated, the unity that contains all diversity, the divine as such.

Two: The Duality, heaven and earth, day and night, the inherent polarity found in the structure of the human world; the ying and yang of ancient China.

Three: The Counterbalance to duality, man + woman + child as the unit of the holy families of Egypt, India, Babylon, and Christianity; thesis, antithesis, and synthesis; the Christian Trinity.

Four: Completeness as in the four seasons, the four winds, the four Stations of the Cross, the four sides of a square. "The river went out of Eden to water the garden; and from thence it was parted, and came into four heads" (Genesis 2:10).

Five: The Defensive Symbol of the pentagram; the five senses, the five wise and foolish virgins. "And he took his staff in his hand and chose him five smooth stones out of the brook and put them in a shepherd's bag..." (Samuel 17:40) .

Six: The Unity of heaven and earth as in the six days of the creation, the six pointed star of David, the six jugs of wine at Cana. "Six years thou shalt sow thy field, and six years shalt thou prune thy vineyard, and gather in the fruit thereof." (Leviticus 25:3).

Seven: The Wholeness and Perfection of the cosmos, e.g. the five planets + Sun + moon; seven lamps of the ark; seven sacraments of the Latin Church; the seven deadly sins and the seven virtues; the Sabbath as the seventh day. "And Balaam said unto Balak, Build me here seven altars and prepare me here seven oxen and seven rams." (Numbers 23:1).

Eight: Another symbol of Completeness as in the eight divisions of the church year, the eight beatitudes of Christ, the eight points of the compass.

Nine: A number of Perfection, three times three forming a perfect square; nine choirs of angels being the famous angelic order of Seraphims, Cherubims, Thrones, Dominions, Virtues, Powers, Principalities, Archangels, and Angels; nine levels of a Chinese pagoda.

Ten: Represents Moderation, ten fingers, ten Commandments, the ten plagues of Egypt, ten curtains of the tabernacle, ten horns of the Apocalyptic dragon.

Eleven: Rarely used although occasionally referred to as in the story of Joseph with his coat of many colours who dreamt of "the sun and the moon and the eleven stars."

Twelve: The Transcendent Symbol - twelve months, the twelve signs of the Zodiac, twelve apostles, the twelve tablets of law in Ancient Rome, twelve tribes of Israel, twelve gates of the heavenly city, twelve years for the completion of childhood.

Thirteen: The number of absolute negativity from Babylonian times.

As we enter the new millennium, it is worth reminding ourselves that icons, made by long forgotten peoples and kept alive by the young painters of today, can point out the way back to our spiritual home, with their forms, colours and eternal truths.